“As a scientist, you are a professional writer.”

This is the opening sentence of the first and the last chapters of the book. It completely changed my perspective on writing. I don’t just write because I must; a writer is who I am. My science is meaningless if it is done and shelved; it needs to be communicated. So, as a scientist, I do science and I write science.

“Writing is story-telling” is the second mandate of the book. In fact, the whole book is about how to tell a story that sticks. Sticky stories have six elements embodied in SUCCES: Simple, Unexpected, Concrete and Credible Stories.

A sticky story is simple so that readers understand. In every good story, there is the simplest idea that can be distilled from the writing (not buried in it). However, simple doesn’t mean simplistic. A simplistic idea is trivial and does not address the core of the problem. The idea that “Streamflow is a complex process” is simplistic. What’s a simple idea then? “Streamflow is governed by climatic inputs and catchment dynamics.”

A sticky story is unexpected so that readers remember. Unexpectedness means novelty, which lies in the reader’s knowledge gap. This gap must be identified first. Tell the reader what he doesn’t know that he doesn’t know. Make him think “Wow, why didn’t I think of that before?”

A sticky story is concrete so that readers can relate to. The ability to bring science’s abstraction down to concrete examples, data and numbers is what separates an expert from a novice. Concreteness is also what separates a good communicator from a bad one. I remember a particular class where the instructor did not give many examples for abstract mathematical concepts; the class was unnecessarily difficult.

A sticky story is credible so that readers believe. “Credibility goes hand in hand with being concrete”, wrote Schimel; both qualities rely on facts, figures, data, and numbers. Credibility can be undermined by buzzwords and hype, lipsticks and make-ups that mask out what is important, so beware of this trap.

A sticky story is emotional so that readers act on it. The number one, perhaps the only one, legitimate emotion in science is curiosity. It is what makes scientists ticks, it is what makes them spend their lives searching for knowledge. A good story must engage the reader’s curiosity by asking good questions.

Lastly, but most importantly, a sticky story has to be a story. It must have characters and plots. Characters are scientific concepts, and plots lie in the story structure. After spending three chapters describing a good story, the book used the next ten chapters to discuss good structures.

There are three main structures for a paper: OCAR (Opening, Challenge, Action, Resolution), LD (Lead, Development) and LDR (Lead, Development, Resolution). OCAR is the most ubiquitous, especially in specialist journals, but LD and LDR are more common in journals with broad audience such as Science and Nature. Let’s see why.

OCAR. In OCAR, the story develops slowly. Schimel compared this with The Lord of the Rings where the characters are first introduced in Chapter 1, then we only get a glimpse of Frodo and Sam’s challenge in Chapter 2, and the full challenge halfway through the first book. The OCAR structure is well suited for a scientific paper because the readers are patient and they want to assess the idea presented properly.

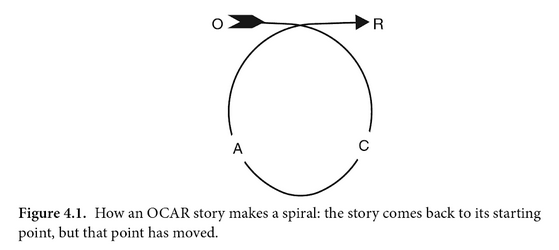

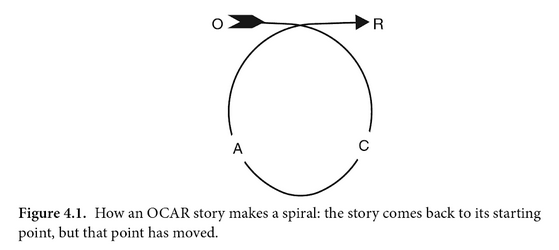

One thing I liked about OCAR is its spiral form (Figure 4.1 in the book). The R must link back to the O. Even more interestingly, OCAR also has an hourglass shape (Figure 4.2 in the book): a wide opening, a narrow challenge and action, and finally a wide resolution. What’s more, the widths of O and R must match. If O is wider than R, we are overpromising and underdelivering. If R is wider than O, we are “underselling”.

LDR and LD. In these two structures, the core of the story, the lead, is loaded in front, and development comes later. With these structures, busy readers are able to grasp the key part of the story without going through its entire development. They may also skip the development if they are not experts in the field, as for the broad audience of Nature and Science.

The story structure does not apply only to the paper as a whole, but for each part of it too. For example, the Introduction most typically follows the OCAR structure while the Results usually follows the LD or LDR structure. Each paragraph in the section has its own structure too. Thus, the internal parts for the paper form story arcs; each arc is a sentence, paragraph or section that tells a story of its own, and they are linked together with fluidity tools such as conjunction and topic/stress formation.

In summary, the two key take home messages for me from the book are (1) that writing science is storytelling and (2) the story structure. I’d like to close this post with a passage from the book that I particularly like.

The need to take multiple passes through a piece, fixing problems as they emerge, explains a frustrating phenomenon I experienced with my advisor, my students have with me, and you probably have as well. You write a draft, someone edits it, and you make those changes. Then, they edit their edits. Sometimes back to the way you had originally written them! Why didn’t they get it right the first time? Are they just changing things to change things? Probably not. Every time you come back to a piece, you need to look at it afresh. Sometimes the changes you scrawled on a sheet of paper or typed in seem okay but don’t really work. You may only realize this when you see the whole new piece or when you read it aloud. Sometimes changes elsewhere in a paragraph mean that you need to rewrite a specific sentence to fit the new structure. Remember the section on “Writing versus Rewriting” in chapter 1. Writing is a process of experimentation and revision; there is no single “right answer.” My last word of consolation on this is that the more you do it, the easier it becomes. It might even become fun.